Higher educational attainment is associated with greater environmental conservation effort.

On this page:

The social benefits of education include environmental conservation[1] and advocacy activities that lead to reductions in pollution, waste, deforestation and biodiversity loss. These activities range from volunteering and political engagement and advocacy to donations and green purchasing. These impacts are positive at a national aggregate level but are difficult to measure at the individual level.[2] Researchers typically measure the behavioural changes rather than the impact.[3],[4],[5] We used the most recent survey of these behaviours.

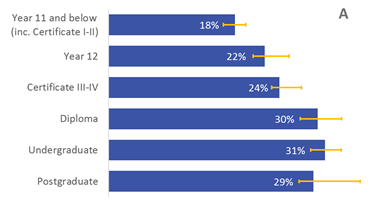

The data shows that, as educational attainment increases, people can be up to two- to four-times more likely to participate in environmental conservation and advocacy activities (Figure 1; Table 1). People with higher levels of educational attainment were also more likely to report that they could be encouraged to get more involved (Table 2). These trends hold after controlling for a wide range of potential confounding factors such as age, income, gender, occupation and where people live (see Data and Methodology).

Figure 1. Proportion of 30-64 year-olds who engaged in environmental conservation advocacy within the last 12 months (A) and, considered the negative effect on the environment when purchasing goods or services (B), by highest level of educational attainment, 2011-12

For insight into what could motivate Australians to greater participation, the predominant response from all education levels was ‘more free time’ at 89 per cent overall. Free time was a marginally greater motivator for people with lower levels of educational attainment, increasing from 84 to 92 per cent (Table 2). ‘More money to contribute’ was not a relatively high motivating factor for participation overall and falls with declining levels of educational attainment. On the face of it, income and other demographic factors do not appear to be the major issue behind lower participation at lower levels of educational attainment. More free time appears to be the most relevant motivator for increased environmental conservation and advocacy at lower levels of educational attainment.

Table 1. The proportion of 30-64 year olds reporting nature conservation and advocacy activities in the last 12 months, by type of activity, by educational attainment, 2011-12

|

Percentage |

Postgraduate |

Undergraduate |

Diploma |

Certificate III/IV |

Year 12 |

Year 11 and below |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Volunteered for nature conservation organisation |

6.7 |

4.1 |

5.2 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

*** |

|

Donated money to conserve nature |

23 |

23 |

21 |

17 |

16 |

12 |

*** |

|

Signed a petition to conserve nature |

15 |

15 |

16 |

13 |

10 |

7 |

*** |

|

Contacted a Member of Parliament to conserve nature |

5.3 |

4.4 |

5.2 |

3.3 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

*** |

|

Unpaid/voluntary nature conservation activities in the last 12 months |

10.1 |

6.1 |

7.2 |

3.4 |

2.9 |

3.0 |

*** |

|

Nature conservation activities at home in the last 12 months |

56 |

55 |

56 |

57 |

48 |

47 |

*** |

|

Paid nature conservation activities in the last 12 months |

3.0 |

3.7 |

3.3 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

1.4 |

** |

Source: Community Engagement with Nature Conservation, Australia, 2011-12 (ABS cat.no. 4602.0)

Notes: Survey weights applied. Statistical significance was tested using logistic regression model combined with propensity score matching (* p<0.1,** p<0.01,*** p<0.001).

Table 2. The proportion of 30-64 year olds reporting that they could be more motivated to become more involved in nature conservation activities, by motivator, by educational attainment, 2011-12.

|

Percentage |

Postgraduate |

Undergraduate |

Diploma |

Certificate III/IV |

Year 12 |

Year 11 and below |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

More free time |

84 |

85 |

89 |

89 |

88 |

92 |

|

Better health |

5.4 |

3.7 |

4.8 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

|

More environmental events in your local area |

15 |

15 |

12 |

9 |

9 |

7 |

|

Seeing the direct benefits of your personal efforts |

11 |

10 |

9 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

|

More information or advertising on environmental issues |

13 |

15 |

11 |

10 |

9 |

7 |

|

Increase in government rebates and incentives |

10.0 |

8.9 |

7.9 |

5.7 |

6.6 |

6.4 |

|

More money to contribute |

7.9 |

7.7 |

7.6 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

5.2 |

Source: Community Engagement with Nature Conservation, Australia, 2011-12 (ABS cat.no. 4602.0)

Data and Methodology

This paper uses data from the ABS’ Community Engagement with Nature Conservation, Australia, 2011-12 (cat. no. 4602.0). This survey was part of the Multipurpose Household Survey (MPHS) where persons were aged 18 years and over (inclusive) and resided in Australia were asked questions about their engagement in environmental participation and conservation activities (N=19,500). To control for confounding factors, a randomised control trial was simulated by finding groups of statistically identical individuals using the following covariates; age, gender, personal and household income, labour force status, occupation, remoteness, Index of relative socioeconomic advantage and disadvantage, English-speaking country of birth and family composition (marital status with or without dependent children)(N=2,267).Significance in outcomes by highest education were assessed with multinomial logistic regression on the matched sub-populations. This provides the strongest possible evidence of cause and effect in cross-sectional data.

[1] Environmental conservation is defined as the protection, maintenance, management, sustainable use, restoration and improvement of Australia’s natural environment.

[2] Kollmuss A & Agyeman J (2002) Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behaviour? Environmental Education Research 8:239-260.

[3] Chapman B & Lounkaeuw K (2015) Measuring the value of externalities from higher education, Higher Education 70:767-785.

[4] McMahon W (2010) The External Benefits of Education, In, Peterson P, Baker E & McGaw B (eds.) International Encyclopaedia of Education pp260-271.

[5] Smith VK (1997) Feedback effects and environmental resources, In, Behrman JR & Stacey N (Eds.), The Social Benefits of Education. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.